Understanding cinematography and how to write shot lists is an essential skill for scriptwriters in the film and television industry.

Knowing shot composition, camera movements, and transitions between scenes adds impactful visual storytelling that successfully transports the audience into the world you’re creating.

This comprehensive guide will break down the most important concepts around shots that every writer should know when developing scripts for film, streaming series, commercials, music videos, and more visual formats.

We’ll also provide critical advice, examples of techniques, and methods for bringing your script from the page to the screen using compelling shot sequences.

Let’s get started understanding the critical importance of shots for scriptwriters!

The Definition and Importance of a “Shot”

What exactly constitutes a “shot” when writing a script intended for the screen?

A shot refers to the continuous footage that is captured in one take by a camera before transitioning or cutting to another viewpoint.

It shows what is happening within a single frame that encompasses part of the scene. The different types of shots combine with cuts and transitions to provide different perspectives to the audience, move the story forward, and set the mood.

Understanding cinematography concepts like framing, camera movement, and shot sequencing allows writers to contribute vital visual details to how a scene can unfold on-screen outside of just the dialogue.

It transforms words on a page into a vivid world for directors and cinematographers to build during production.

Scripts that incorporate thoughtful shot descriptions give filmmakers an impactful skeleton to put meat on the bones.

That’s why the most effective scriptwriters have a deep understanding of shots – it enables them to showcase both writing and visual storytelling abilities.

Mastering shot terminology and technique signifies an ambitious writer willing to become a filmmaker’s trusted collaborative partner. Let’s explore the array of shots at your disposal to make that possible!

Deciphering the Shot Types Screenwriters Utilize

Below we’ll provide definitions and typical uses for common types of shots that scriptwriters incorporate into their screenplays:

Extreme Close Ups (XCUs)

Extreme close ups, sometimes called “punch-ins”, provide the audience with an ultra-tight focus on small details and intimate emotions.

For example, an extreme close-up could show tears welling in a character’s eyes, tension in their jaw muscles, or hands trembling with anger.

XCUs build intensity or emphasize emotional weight. Use them sparingly for brief impact.

Close Ups (CUs)

A close-up shot frames the face or upper body portion of a character, subject, or significant detail.

It eliminates surrounding distractions to focus attention on expression and psychology. Close-ups allow the viewer to study emotions and reactions from up-close. Use CUs for impactful dialogue exchanges and solos.

Medium Close Ups (MCUs)

Medium close-ups widen the framing from a typical close-up to include the head and shoulders of a character within the shot composition.

The intention is still an intimate focus on facial expressions and emotion, but with a touch more environmental context. MCUs add a balance of insight and scenery.

Mid Shots (MS)

A mid shot reveals a character from the waist or chest up, retaining facial elements critical for emotive effect while expanding the visible setting.

Mid shots communicate physicality and environment to complement dialogue and performances. They orient the audience to relationships between characters and their location.

Full Shots (FS)

As the name suggests, a full shot displays the entire body of a character and maximal surrounding scenery that sets the tone, ambiance, and context.

It pulls back from an overt focus on expressions for greater environmental absorption while keeping figures recognizable. Full shots provide breadth, locale establishment, and a rest stop from close-ups.

Extreme Long Shots (ELS)

On the opposite end of the spectrum from XCUs, extreme long shots convey expansive scenery and geography from an extreme distance.

It dwarfs any characters on screen while highlighting lush, sweeping location visuals. Think horizon lines where land meets the sky. ELS are largely used to establish grand settings and provide Wise epic scope.

High Angle Shots

The camera looks down upon the subject from an elevated angle above the eye line, making the viewer peering down into the scene.

High angles reduce and diminish power, evoking vulnerability, weakness, youth, or the immensity of the environment. Hitchcock used high angles to make characters seem small and powerless against harsh surroundings.

Low Angle Shots

Contrary to high angles, in low angles the camera gazes upwards from below the eye line, angling a character or setting against the sky.

Low angles exaggerate importance, dominance, strength, and imposing natures. Use low angles sparingly to heroize or intensify the impact.

POV Shots

POV, or point-of-view shots, provide the viewer with a literal look through the eyes of a character onto surrounding story events.

The audience directly feels what a character is seeing in real-time. Write POV shots into intense moments as on-screen experiential catalysts.

It grounds the audience in unrelatable scenarios to comprehend the environments and emotions at play.

Beyond individual shot types, great scriptwriting also means strategically transitioning between different shots to maximize visual dynamism. Let’s analyze some of the most popular shot transitions employed in scripts and final cuts.

Scriptwriting Shot Transitions and Scene Continuity

Basic Cuts

The most straightforward shot transition is a basic cut between shots. It’s an instantaneous change from the viewpoint of one shot to another without gradual transition effects applied.

Cuts cleanly and efficiently move the story’s focal point to new subjects and scenery essential to the plot. Intersperse cuts frequently when writing to avoid lingering on similar framings too long.

Fades

A fade gradually transitions a preceding shot into complete blackness before fading back up from black into the subsequent shot.

Fading to black suggests the passage of time or the symbolic conclusion of a scene, memory, or emotion.

It can indicate a major shift in narrative time and mood. Use fades sparingly yet purposefully to demark thematic changes over time.

Wipes

A wipe manifests when the initial shot is replaced by the incoming shot through a boundary line moving across or descending upon the screen to “wipe away” the previous imagery.

Think sliding doors or curtain drapes peeling back. Wipes reflect dynamic thematic shifts in time, place, and tone between scenes. Feature them during pivotal story flashes or location changes.

Dissolves

Dissolves blend two disparate shots together simultaneously, with one image fading out as the other overlaps and solidifies it in transparency.

Dissolves smooth time ellipses, signify dream sequences, or parallels between characters or memories. Dissolves demonstrate symbolic or plot-wise connections between shots.

Knowing proper vocab empowers scriptwriters to dictate shot sequencing and scene continuity that aligns with the directorial vision. Now let’s analyze constructing compelling scenes through shots.

Composing Compelling Scenes With Shots

Great scriptwriters utilize shots not only to establish physical setting and blocking but also as vessels for layered story enhancement via visual analogy and metaphor.

Vary framing sizes, angles, and movement styles depend on the mood your script seeks to convey per scene.

Long dolly shots expand scenery slowly to expose new environs impacting characters, while fast whip pans induce disorientation.

Match shot intensity to the emotional weight or action events unfolding within a sequence. Frenzied dialogue exchanges cut rapidly between alternating close-ups.

Funeral scenes dwell in sustained wide shots swallowing solitary characters against nature. Build atmospheric density through patient full shots before relieving pressure in closer perspectives.

Script entire story beats around impactful sequences conveyed through specialized shots. Imagine critical memories playing out entirely in slow-motion crosscutting.

Or flash forwards constructed from quicker cuts than the timeline setup preceding it as the “new normal”.

Maybe an assault scene where the victim fades between the attacker’s violence and their brother’s kindness to escape mentally. Shots become vessels for contextual enhancement.

For example, Steven Spielberg and DP Janusz Kamiński designed the baptism scene in The Godfather to intercut between Michael renouncing Satan as his new Godson’s official Corleone father and his men simultaneously executing rival mob bosses on his command.

The religious ceremony and murder sequences cut rapidly heighten narrative stakes through visual juxtaposition of Michael’s ascent from civilian refugee to ruthless don.

Every scene consists of cinematic syntax – purposeful shot selection reflecting context. Master scriptwriters pen beyond location and actions to motives. They think in framings that will later direct audience’s attention.

Let’s now cover some easily avoided missteps to dodge en route to excellent directing in script form.

Common Shot-Related Mistakes Writers Make

Before graduating to proficient shot direction within screenplays, make sure to sidestep these snags that novices encounter:

Abusing Certain Shot Types:

Every shot framing bears a purposeful place. But some beginners overutilize close-ups and medium shots even when story priorities dictate wide full-scene coverage.

They forget four people conversing mid-argument requires distance to capture reactions. Relying exclusively on close-ups disorients the audience. Variety fosters perspective.

Disorienting Shot Orders:

Bouncing from POV to extreme close-ups to long shots randomly annoys audiences struggling to latch onto contexts.

The shot sequencing should flow intuitively to ground viewers quickly. Jarring shots must hold a narrative purpose, and not be confused simply because they sound artsy. Orient viewers before shocking them through abnormal transitions.

Odd Transitions and Cuts

Avoid flashy transitions like star wipes or irregular dissolved colors purely for spectacle – they distract from the plot progression at hand.

Similarly, cutting on the action axis jumps broadside viewers. Define blocking and positioning first before crossing the line. Shots exist to progress stories, not show off trickery. Substance over style.

Pacing Scenes Too Slow or Quick:

Dragging long takes beyond necessity diminishes dramatic impact while rushing through dense dialogue denies viewers room to observe subtleties.

Set shot lengths and cut rates consistent with the mood portrayed – tranquil conversation scenes hold shots to let performances breathe, while gunfights incorporate shorter bursts mirroring their intensity. Match your shots’ pacing to scene pacing.

With common mistakes covered, let’s outline efficient processes for incorporating shots into scripts.

Best Practices For Writing Better Shots

Now that we’ve broken down shots extensively, how do screenwriters implement this visually focused knowledge? Follow these handy methods:

Use Shot/Scene Description Softwares

Dedicated screenwriting software like Final Draft automatically formats scene headings, transitions, and shot descriptions correctly.

Specialized templates streamline organizing critical script shooting elements so writers focus on the story not structure.

Plan Shot Lists Before Drafting

Strategize which impactful plot turns and character moments will happen on screen before actual scripting.

List key sequences with desired shot types mapped sequentially. This clarifies visual narratives beforehand.

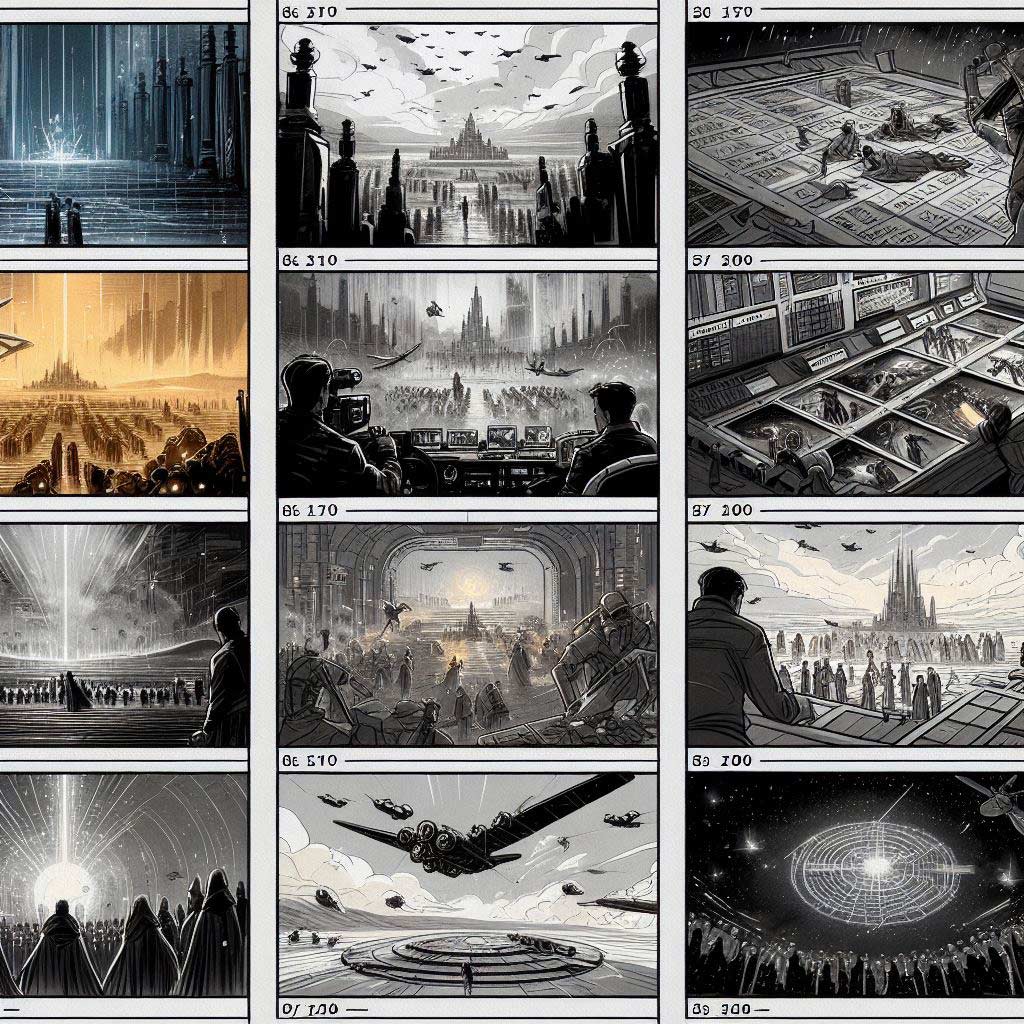

Storyboard Important Scenes

Storyboards illustrate script events literally panel-by-panel. Sketching critical scenes’ separate shots grants innate spatial understanding to then write cleanly within screenplay format. It also provides “blueprints” when pitching directors.

Collaborate With Directors

Attach directors early before completing script drafts, sharing storyboards, and taking notes. Directors visualize shot sequences inherently.

Involving them ahead enriches shot relevance, positioning, continuities, and dramatic resolutions.

Remember that shot design starts way before actual filming begins. Scriptwriting builds the all-important visual sequence backbone for directors to then construct around during production. Do the heavy narrative lifting early through strategic shots detailed enough for others to faithfully translate on set later.

Key Takeaways

We’ve only illuminated the storytelling tip of the cinematic iceberg today. But absorbing core shot methodology starts every screenwriter on a path toward visually focused scripts that manifest on screen effectively.

To recap key learnings:

- Shots frame on-screen perspectives that cut together to drive movie narratives

- Shot types dictate scope from intimate extremes to distant establishers

- Cuts and transitional effects bridge shots smoothly or abruptly per story needs

- Sequences interweave shots carrying symbolic/metaphorical weight

- Pacing shots’ continuity and length set scene intensity accurately

- Mistakes stem from poor shot structuring and continuity establishment

- Writing better shots requires planning via lists, storyboards, software

Armed with this diverse cinematic vocabulary, screenwriters can now deliberately dictate impactful blocking, emotion-heightening angles, and perspective seamlessness shot-by-shot.

Confidently convey imaginative directorial choices through the written word. Then watch your vision translate authentically through shots when produced on set.

Dive deeper into the craft by studying incredible cinematographers’ shot-shining moments. Let visual media enrich writing instincts.

Soon shot sequences will flow freely from mind to script, communicating both stories and the beating hearts behind them.

You may now possess the knowledge needed to evolve written words from flat simulations of life to experiential portals into lived moments.

Wield the full force of shots purposefully to transport audiences into fully-manifested worlds that leave indelible impacts.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you write a shot in a script?

When writing shots in a script, you include the type of shot such as CLOSE UP, WIDE SHOT, ESTABLISHING SHOT, etc. before the scene description. For example:

WIDE SHOT of the busy newsroom as reporters scramble to meet deadlines. JANE, 25, walks through carrying photos.

What is the difference between a shot and a scene in a screenplay?

A scene is a complete unit of story action, while a shot shows the visual framing from within that action. Scenes have scene headings and contain multiple shots that cut between different perspectives.

What does establishing shot mean in a script?

An ESTABLISHING SHOT in a script sets up the audience within a location, revealing the scene’s setting. It provides a wide visual scope to establish the scene’s time, place, environment, and mood before cutting into closer shots of details and characters.

How do you write a POV shot in a script?

To write a point-of-view (POV) shot in a script, you include “POV” or “FROM JOHN’S POV” before the description to indicate we share a specific character’s visual perspective. Ex: FROM JANE’S POV, she sees a car speeding towards her. Describe what Jane sees through her viewpoint.

Do you put shots in a script?

Yes, effective scriptwriting involves thoughtful inclusion of planned shot descriptions, camera angles, shot sequencing, and transitions to direct key story moments with compelling visuals suited to the screen.

Are shots included in script?

Shots should be included strategically throughout scripts to establish settings visually, follow or reveal characters, transition between scenes, and underscore the emotional impact of important story scenes when adapted to film.

What is a scene shot?

There is no specially termed “scene shot” – this would simply refer to the variety of shots composed to capture the action within a full scene of a screenplay after it enters production. This includes establishing shots, close-ups, wide shots, completely new perspectives, etc used to portray the scripted scene.

What are scenes and shots?

Scenes contain complete segments of story action in scripts and films, while shots are the individual camera viewpoints framed within the filmed depictions of each full scene to provide angles on the locations, characters, and events within them through editing.

What are scenes in a script?

Scenes in a script compartmentalize all the events happening in one location at one time as the story progresses. Scene headings indicate settings. Scenes may consist of narration, action description lines, dialogue exchanges between present characters, and shot descriptions for key visual moments the writer wishes to highlight.